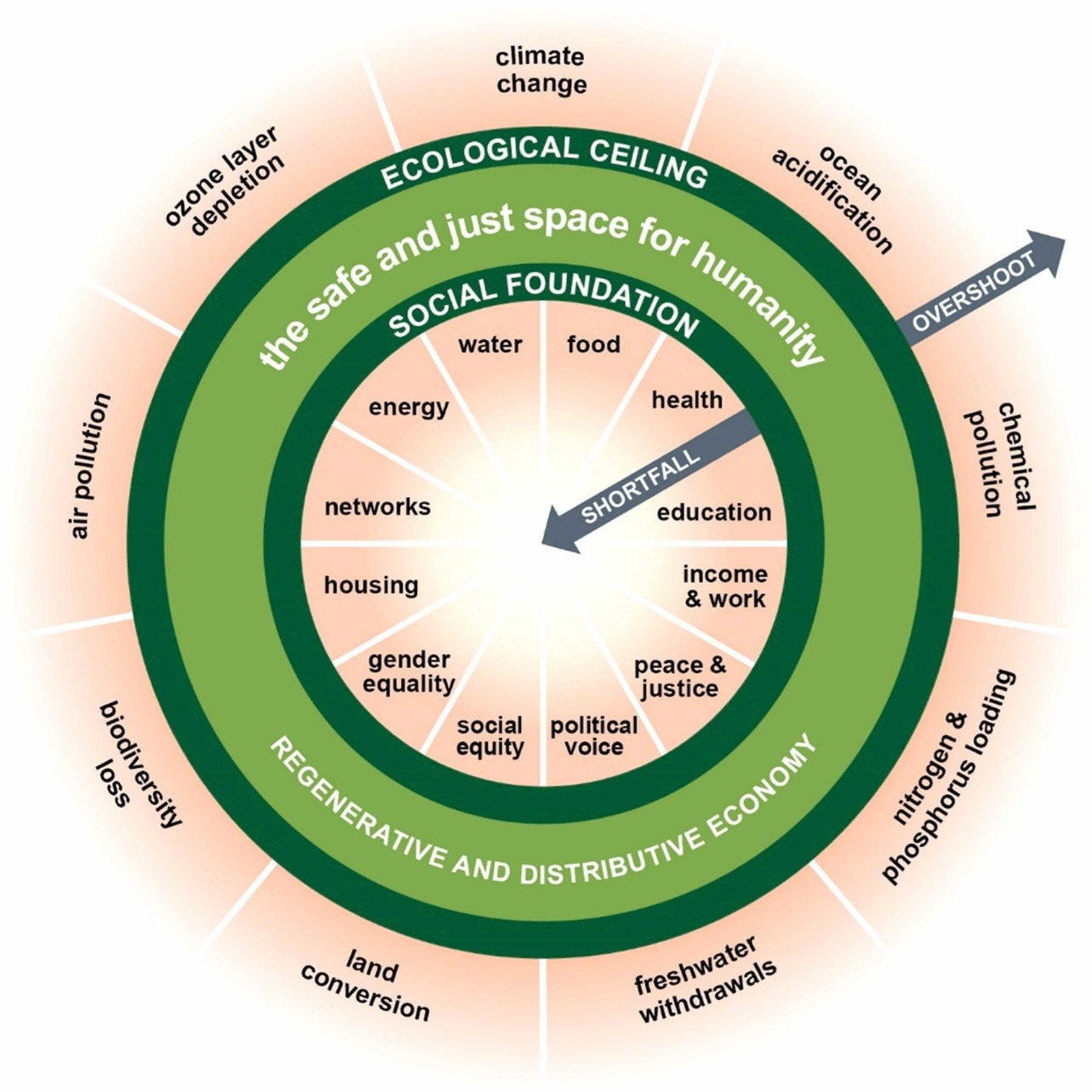

A just socio-ecological transformation may be understood as a transformation ensuring “a good life for all within planetary boundaries” (O’Neill et al., 2018). This implies meeting basic human needs while remaining within ecological limits as delineated by the planetary boundaries framework. The area in which both objectives are satisfied has been described as “a safe and just operating space for humanity” (SJOS), a concept developed most prominently in Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics.

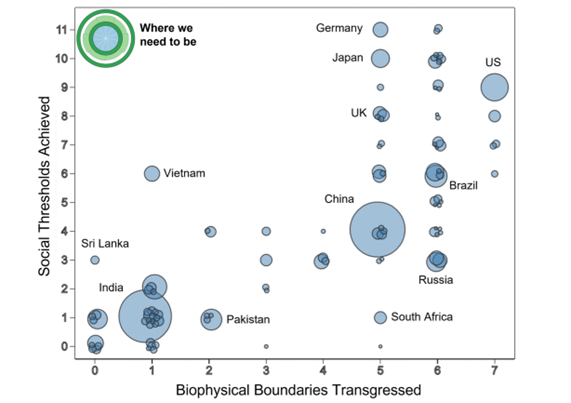

If this framework is applied to contemporary nation-states, it shows that no country has yet managed to meet basic social thresholds at a globally sustainable level of resource use (Fanning et al, 2022).

Nevertheless, this does not imply that achieving such a state is impossible. Recent studies indicate that human needs satisfaction within ecological limits could be feasible even for a global population of 8 to 10.4 billion, provided that ambitious sufficiency strategies are adopted, especially in high-income countries, and that significant changes occur in the provisioning systems of the foundational economy (Schlesier et al., 2024; Hickel/Sullivan, 2024).

Shortcomings of mainstream transformation approaches

Several mainstream approaches have been advanced to guide socio-ecological transformation. However, their suitability for delivering deep structural change can be contested.

Market-based instruments like carbon pricing remain central to policy discourse, but their effectiveness is limited. Even if they were applied more consequently, such measures face “price-resistant barriers” in sectors like energy and transport (Kemfert et al., 2021), and have limited relevance for ecological domains such as biodiversity or land use (Schaupp, 2024; pg 283). Without social safeguards, they also deepen inequality (Schaupp, 2021).

Green growth strategies rely on decoupling GDP from environmental impacts, yet current rates of decoupling (~2.5% annually) are far too slow. Vogel and Hickel (2023) estimate that a tenfold increase in decoupling rates would be required by 2025 to meet the 1.5°C target. This casts serious doubt on green growth as a viable central strategy.

More state-centred than these models is the Mission Economy approach (Mazzucato et al., 2019) that has some influence in the EU (EU COM, 2021; EU COM, 2023). The model focuses on state-led innovation and market-shaping, focused on sustainability challenges. While this marks a shift from minimalist state roles, it remains too loosely tied to the planetary boundaries.

The Limits of Progressive Localism

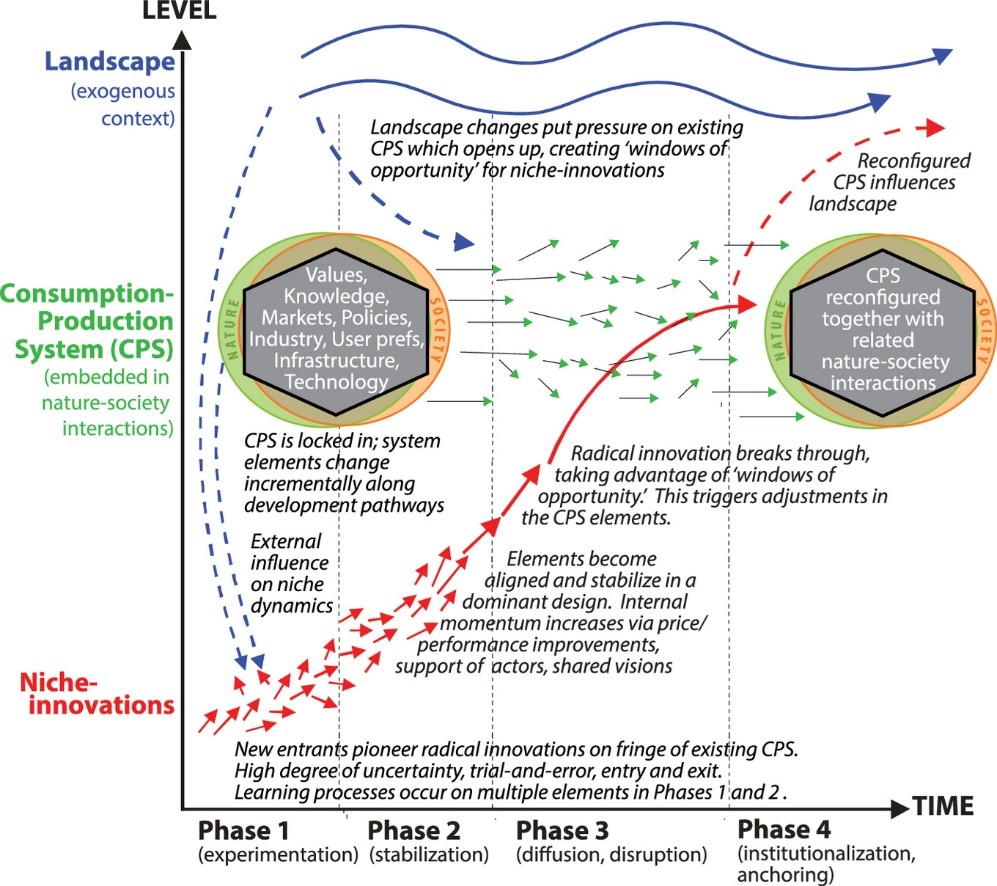

Progressive localism highlights the undoubtedly valuable transformative potential of local initiatives in the foundational economy (like housing, transport or food systems). Yet the systemic impact is limited, too: Initiatives often remain disconnected from national frameworks, target low-hanging fruits and have no plausible concept for scaling up to a grand transformation. Furthermore, they often evolve in parallel with, rather than displacing, ecologically damaging activities (Vettese & Pendergrass, 2022; pg 14). Concepts that essentially view transformation as originating from niche innovations are therefore likely to be inadequate.

The Case for Democratic Planning

Given the limits of current approaches, more coordinated governance is gaining interest, particularly democratic planning. This involves the strategic alignment of production with ecological and social goals. It becomes particularly crucial in degrowth scenarios, where resource use must shrink intentionally. As Hickel and Sullivan (2024; pg 7) observe:

“This is challenging within a capitalist market economy […] because any reduction of aggregate output triggers social crises characterized by mass layoffs and unemployment. Furthermore, under capitalism, decisions about production are made by wealthy investors with the primary goal of maximizing private profits, rather than meeting social and ecological goals. Necessary goods and services that are not profitable are often underproduced. Post-capitalist approaches are therefore needed […].”

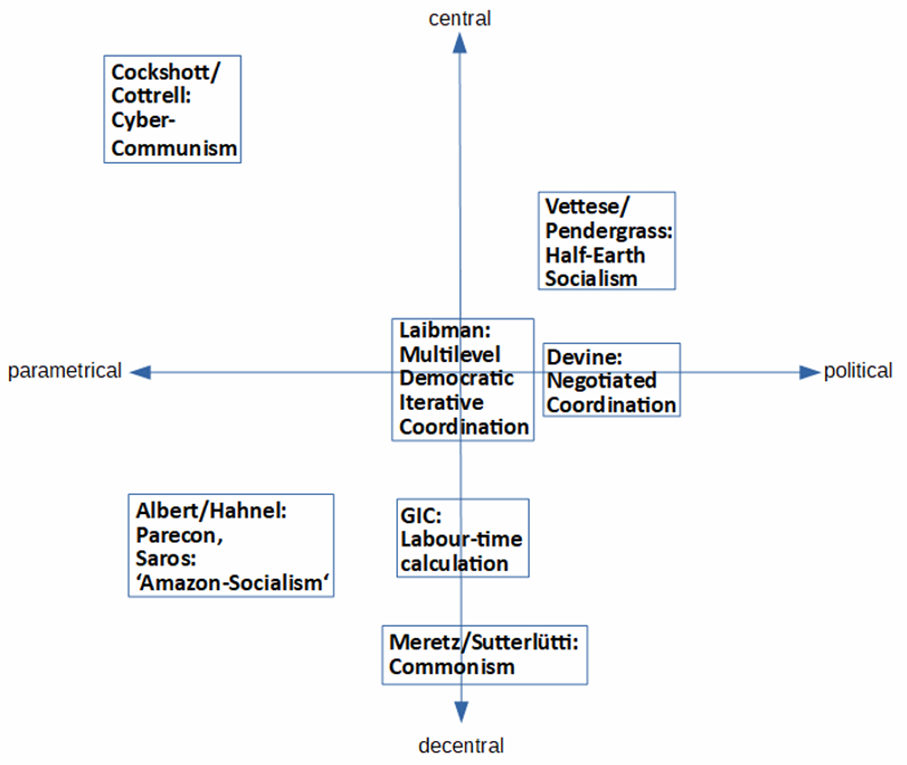

A range of planning models have recently re-entered academic debate, from models proposing capitalist planning (e.g. Herrmann, 2022) to models that go beyond a capitalist economy (see Heyer, 2024 and Groos/Sorg, 2025 for an overview). Some of these models start from historical experiences with war economies, where in a short period of time, production and societies had to be reorganised (Delina, 2016; Malm, 2020). Planning models can be distinguished by their degree of centralisation and by whether coordination is algorithmic (parametric) or deliberative (political).

Each of these raises normative and practical questions about institutional design, legitimacy, and spatial differentiation. However, it seems quite clear that any reasonable transformation model has to provide means to align planetary boundaries with social needs. It is hard to imagine how this can be done without new forms of planned economies (Zeug et al., 2021).

Regional Dimensions and Research Agendas

For regional studies, these observations raise important empirical and theoretical questions. Uneven development and spatial inequalities, such as those found in France’s “Empty Diagonal” or the UK’s “Broken Heartlands” (Payne, 2021), underscore the need for spatially sensitive approaches. Current modes of the socio-ecological transformation tend to increase spatial inequalities and the burdens for vulnerable groups and regions as they tend to destroy what has been called to ‘fossil class compromise’ that involved substantial benefits for the hinterland in the global north (Schaupp, 2021). Research in this field is therefore well-placed to contribute to understanding the institutional capacities, spatial logics, and democratic potentials of post-growth planning. Clarifying the possible roles and configurations of the state in this context may be essential to ensuring that socio-ecological transformation is both effective and just.

This blog post is based on the presentation “Perceptions of the State’s Role in a just Socio-ecological Transformation” at the 2024 RSA Winter Conference in London, Special Session 02 “Promoting Justice for Eco-social Transformations in Urban and Regional Development: Perspectives from Theory and Practice”, organised by the RSA’s Research Network on Eco-Social Policy and PRactice for Innovation and Transformation (ESPPRIT)

Connect with the Author

Dominik Gager has held the position of “Professor of Sustainability Transformation, particularly in the public sector” at Darmstadt University of Applied Science since January 2023. His focus in teaching, research and transfer is the eco-social transformation. He works particularly in fields such as climate mitigation and adaptation, spatial planning/land use and the integrity of the biosphere, as well as the equity issues associated with the transformation. In addition to his experience in scientific research projects on these topics, Dominik worked for five years in public administration in the areas of climate, environment and sustainable development, most recently as head of a municipal office for environment and climate protection.

![]() : https://fbw.h-da.de/en/gager

: https://fbw.h-da.de/en/gager ![]() : Dominik Ganger

: Dominik Ganger ![]() : 0000-0002-5032-2644

: 0000-0002-5032-2644