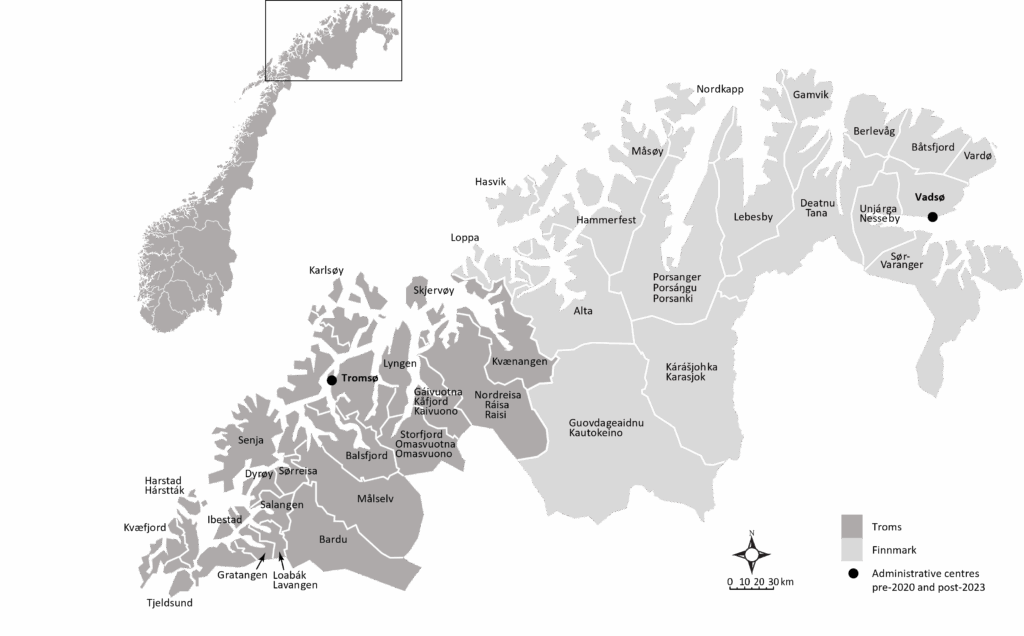

The failure of the merger, whether or not one agrees with its implementation in the first place, can in part be traced to insufficient consideration of the region’s history. In its reasoning for the reform, the government addressed the benefits of larger, more populous regions primarily in terms of increased efficiency. Identity-based regionalism was brushed aside on the basis that interest in regional democracy is comparatively lower than municipal democracy (Gulbrandsen, 2023). This was a dangerous conflation to make regarding Finnmark, whose history of institutionalisation and incorporation into the Norwegian state made it a battleground for resistance to the merger (Gulbrandsen, 2024).

As a place name, Finnmark (Finnmǫrk in Old Norse) first referred to an area inhabited by the indigenous Sámi stretching across the northern and central parts of modern-day Norway, Sweden, Finland, and (Northwestern) Russia (Berg-Nordlie, 2021). The area was not considered to be part of Norway, but rather an “immeasurably wide” area to the north of it, encompassing “almost the entire interior as far south as Hålogaland along the coast” as famously described in Egil Skallagrimsson’s saga from the 1200s (quoted in Kjelen, 2022: 19-20).

Throughout the Middle Ages, Finnmark, whose name eventually referred to a smaller area, became increasingly integrated into wider geopolitical relations through expanding Norse settlements. This took on an increasingly systematic character in the mid-16th century, when the colonial incorporation of Sámi land into the then Danish-Norwegian state became a central priority to defend territorial claims against neighbouring states (Hansen & Olsen, 2006; Hagen, 2019; Berg-Nordlie, 2021). With the inclusion of Kautokeino and Karasjok in 1751 and Sør-Varanger in 1826, the entirety of modern-day Finnmark was formally incorporated into Norway.

Meanwhile, irrespective of contested borders, the establishment of Finnmark as an administrative unit within the state under the name Vardøhus dates back to 1576. Vardøhus was later expanded in 1787 (mirroring the merger of 2020) and received the name “Finnmarken” in the process. When Finnmarken was later dissolved in 1866, the name remained attached to what is Finnmark today.

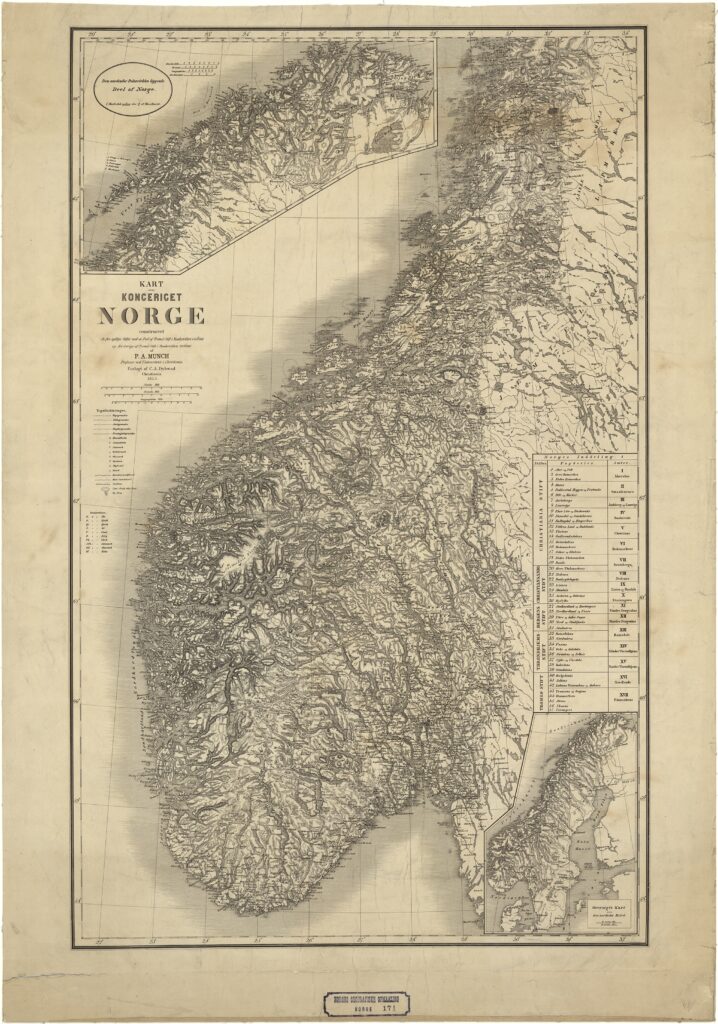

A map from 1855 signals how the Norwegian authorities viewed the region at the time (Figure 2). While the map offered a cartographic representation of a unified Norway, the tradition of drawing the north (associated with indigenous and minority populations) at half the scale of the rest of the country also revealed the incompleteness of this process (Selstad, 2003).

Indeed, the settlement of state borders did not end the Norwegian state’s attempts to neutralise perceived threats. The broader North Norwegian regionalist ‘project’ which first emerged in the second half of the 1800s was in many ways “an extension of and giving greater depth to nation-building and nationalism” – even the name itself suggested that the north was firmly Norwegian (Niemi, 2007: 83, 2009). This reflected the Norwegian state’s maintenance of an active assimilation policy of ‘Norwegianization’ towards indigenous and minority populations from around 1850. The policy aimed to actively limit the use of Sámi and Kven languages and enforced ethnic discrimination regarding land (Minde, 2003; NOU 1994: 21).

A shift in state policy eventually took place when conflict over hydropower development in core Sámi areas of Finnmark erupted in the late 1970s and early 1980s (Eira, 2013). This resulted in the subsequent establishment of the Sámi Parliament in 1989, Norway’s ratification of the ILO Convention on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in 1990, and the 2006 transfer of 95% of Finnmark’s area from a state-owned enterprise to a regional landowning body. The policy of Norwegianization has nonetheless had lasting impacts that continue to influence debates on identity, interests, and rights in Finnmark today.

On the background of Finnmark’s history of domination by the national state (and, though too much to cover here, its political and economic peripheralization in several other respects), it should come as no surprise that regional history and identity were actively mobilised by those opposed to the merger in 2020. Direct lines were drawn between the merger and earlier examples of state coercion that could resonate with lived experience and generational memory. As a consequence, the official portrayal of the regional scale as devoid of cultural and political attachment fell flat in Finnmark. The government’s insufficient attention to Finnmark’s historical institutionalisation and consideration of the material and immaterial consequences of implementing a merger without local legitimacy opened up space for powerful ‘counter-institutionalisations’ to emerge from below (Gulbrandsen, 2025).

Three interconnected lessons arise from the failure of the Troms-Finnmark merger. Firstly, efficiency-based spatial imaginaries do not necessarily make for convincing regional visions, especially when they are full of contradictions (see the exclusion of the capital Oslo from the reform as a case in point). Secondly, ignoring identity-based regionalism or confusing lived identity with election turnout poses risks of its own (and easy fodder for local counter-institutionalisation). Finally, failing to secure a broad democratic consensus for the reform in general, and neglecting to seek local democratic legitimacy for the merger, threaten such initiatives from the outset. The Troms-Finnmark merger highlights that without attention to local identity and history, a regional reform motivated solely by economic efficiency can soon become a source of bureaucratic waste.

Additional Read

Gulbrandsen, K. S. (2024). Political geographies of region work. [Doctoral Thesis (monograph), Human

Geography]. Lund University.

Connect with the Author

Kristin Smette Gulbrandsen is a political geographer with a research interest in processes of regional emergence and transformation. She holds a PhD degree in Human Geography from Lund University, where she studied state-led regionalisation and local contestation in northern Norway. Currently, she is a postdoctoral researcher at University of Copenhagen, Department of Political Science, where her research explores democratic innovation and citizen engagement in spatially uneven renewable energy transitions.