Can devolution address these spatial inequalities?

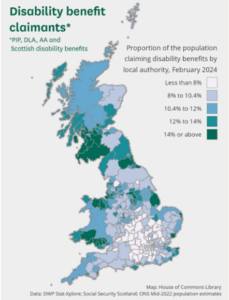

This uneven geographical distribution of disability benefits and the shadow of deindustrialisation also underpins a dominant economic rationale for increasing devolution in England:

… the [English] ‘devolution agenda’ is framed as an antidote to widening socio-economic inequalities between and within regions and the discontent that has grown in ‘left behind’ places (Warner et al 2024: 736)

The English Devolution White Paper (2024) sets out three key drivers for devolution:(1) economic growth, (2) joined-up delivery of services and (3) the democratic involvement of communities (Hickson Newman, 2025). The remainder of this blog argues for a loosening of the tie binding economic growth, economic outcomes and devolution.

(1) Economic growth, reduced public spending, and increased employment rates are central goals of Pathways to Work. However, these ambitions may fall short. While the 2010–12 welfare reforms cut disability benefit spending by £650 million annually—a notable reduction—it was far below the projected £4.35 billion (Beatty and Fothergill 2018: 11). Furthermore, the belief that welfare reforms automatically lead to higher employment among disabled people is problematic, particularly in areas where structural barriers persist:

“the idea that welfare reform will trigger additional employment is rooted in a particular view of how an economy works… At times and in places where an economy is operating at or close to full employment this argument has some validity… in places where there is a substantial surplus of labour [this assumption] is more problematic.” (Beatty and Fothergill 2018: 16)

Pathways to Work makes some of the same assumptions. However, in terms of (2) joined-up delivery of services, Local leaders and employers are positioned as key to reducing economic inactivity through greater collaboration (Pathways to Work 2025: 49). Thus, current reforms identify support mechanisms and investments which could go further than the explicit aim of reducing so-called ‘welfare dependency’.

Finally, on the (3) democratic involvement of communities within the English Devolution White Paper, “there is a lot of rhetoric about ‘empowering communities’, [however], the only policy to enact this is about allowing communities to buy certain assets.” (Hickson and Newman 2025: 6). Indeed, by underpinning ‘joined-up services’ and ‘community involvement’ with economic growth (and arguably continuing an ‘austerity model’ to economic development- see Etherington, Gray and Buckner, 2025), an opportunity is missed for more ambitious visions of democratic renewal and community empowerment that may be possible including community and participatory centred public service reforms.

Instrumentalising devolution for economic aims frames decentralisation as a technocratic process. It also stakes the success of devolution on particular kinds of economic outcomes, which are often out of local and subnational control. This is potentially problematic for English devolution, arguably making it hostage to economic fortune, which in turn is a risky strategy for public trust in democracy (Hickson & Newman, 2025). This is especially problematic if devolution becomes viewed as economic risk-shifting rather than politically empowering.

Devolution needs to be about more than economic development

While economic growth and better public services are aspects of devolution-in-practice, the devolution projects in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have been more than an economic growth strategy. In Scotland and Wales, the expansion of devolved powers over the decades rests on demands for better representation for the Scottish and Welsh populations and associated increased power (realised through the Smith Commission, the Scotland Acts 2016 and 2018, and the Silk Commission, resulting in tax-raising powers for Wales).

As Pathways to Work rolls out across the UK, widening the English devolution narrative to rest on alternative ideological aims and to loosen the tie binding economic growth and place-building should be encouraged. In so-called ‘left behind places’, trust in government is wearing thin and the far-right Reform Party are gaining ground. These are the places where the highest losses from disability welfare reforms may be seen and perhaps where alternative values based on community wellbeing, dignity, respect, and social investment might be more important outcomes to foster and measure.

Acknowledgement

This paper is drawn from the Safety Nets project. This project has been funded by the Nuffield Foundation, but the views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

The project examines the way devolution of social security within the UK shapes realities, risks, and opportunities for families with dependent children. It is a multi-institutional and inter-disciplinary research and policy team comprised of academics from six universities across all four UK nations, the Resolution Foundation, and the Child Poverty Action Group.

Connect with the Authors

Sioned Pearce is a Lecturer in Social Policy at the School of Social Sciences, Cardiff University. Her research focuses on how devolution and devolved social policies are reshaping work and welfare across the UK.

Hayley Bennett is a Lecturer in social policy at the School of Social and Political Science, University of Edinburgh.

Mhairi-Jean Ross is a Research Associate at the University of York at the Changing Realities Project, the UK’s leading participatory research project documenting the experiences of UK parents on low incomes.

Ruth Patrick is Professor of Social Policy at the University of York and the Principal Investigator of the Benefit Changes and Larger Families research programme.