Child poverty is regarded as a multidimensional, yet heavily economically based phenomenon. Previous studies on the UK or OECD countries underline the role of low income, job insecurity and worklessness, especially in lone-parent and minority households (Bradshaw, 2002; Thevenon et al., 2018). Additionally, in-work poverty is rising, and other factors, like housing, parental health and alcohol or drug dependency, contribute (NECPC, 2024).

Newcastle upon Tyne is recognised for having one of the strongest economic performances in the North East of England (ONS Subnational Indicators). However, despite its economic success, Newcastle also faces one of the highest rates of child poverty in the region. This paradox raises a critical question: Why does child poverty persist in a city with positive economic indicators?

This blog post seeks to explore this issue by examining key economic indicators and the underlying drivers of child poverty.

To begin, a closer look at the economic data is essential. While Newcastle excels in terms of average pay levels, it performs less favourably in other areas, particularly economic inactivity. Statistical analysis highlights a strong relationship between economic inactivity, low pay, and child poverty.

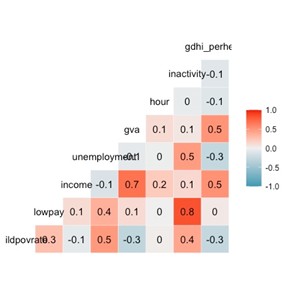

Figure 1 presents a heatmap showing the correlations among several key variables, including child poverty rates, low pay, income, unemployment, gross value added (GVA), economic inactivity, and household income. This visualisation underscores the interconnected nature of these factors and suggests that tackling child poverty in Newcastle requires addressing broader structural issues, such as economic inactivity[1].

Figure 1 – Heatmap with correlations

Source: Data from ONS and DWP

Health plays a critical role in economic inactivity, underscoring that economics cannot be understood through economic indicators alone. Data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) highlights a troubling trend: between 2019 and 2023, the number of individuals economically inactive due to long-term sickness has increased significantly. This rise in ill health as a driver of economic inactivity has profound implications for understanding child poverty.

The connection between health, deprivation, and child poverty proves that addressing poverty requires a multidimensional approach—one that goes beyond traditional economic measures to include investments in public health and social support systems.

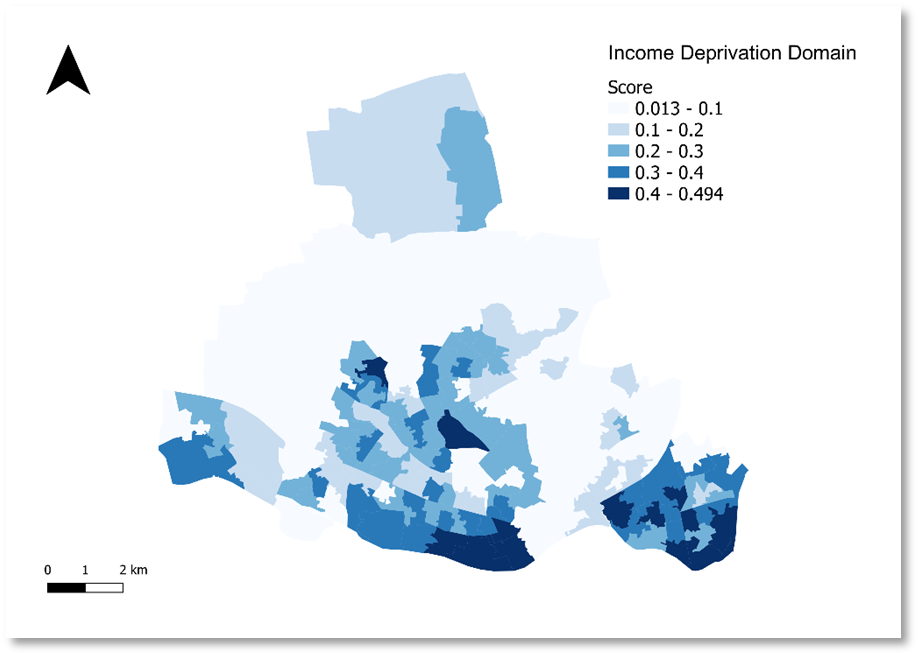

Second, local inequalities are crucial to understanding the persistence of child poverty in Newcastle. While the city performs well overall, it is also characterised by significant disparities, with “poverty pockets” concentrated in specific areas. These localised inequalities highlight that strong economic performance at the city level can mask deep-rooted deprivation within certain communities.

Figure 2 provides a visual representation of this issue through a map of Newcastle, illustrating income deprivation scores from 2019. The map reveals stark contrasts within the city, emphasising the uneven distribution of economic prosperity and the need for targeted interventions in the most deprived neighbourhoods.

Figure 2 – Income Deprivation (2019)

Finally, this evidence underscores the methodological challenges inherent in analysing child poverty. As a multidimensional phenomenon, child poverty cannot be fully understood through linear statistical tests alone. Capturing the complex causal relationships between its drivers and outcomes requires more sophisticated analytical approaches that account for the interplay of social, economic, and health-related factors.

For effective policy evaluation, quantitative methods must be complemented by qualitative approaches, such as exploring the lived experiences of those directly affected by poverty. These insights provide a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by beneficiaries, which cannot be fully captured through quantitative data alone. Local data also presents notable gaps, particularly in its lack of granularity and reliable proxies for understanding the relationship between pay and poverty. Greater precision in local-level data is essential to identify the nuanced dynamics of poverty and to design policies that effectively address the specific needs of different communities.

In terms of policy implications, there is a clear need for more targeted and context-specific interventions. Addressing the root causes of child poverty requires policies that focus not only on income but also on health, education, and local inequalities to create sustainable and inclusive solutions. Although insufficient to fully resolve the issue, these measures represent important first steps towards understanding and addressing this complex puzzle.

[1] Description of variables. Child poverty (DWP): child poverty rate, calculated by the percentage of children aged 0-15 living in relatively low-income households (a family with a low income before Housing Costs in the financial year). Low pay (ONS): The estimated number of employee jobs with hourly pay excluding overtime and shift premium pay below the living wage by parliamentary constituency (work-based geography). Unemployment (Annual Population Survey/Labour Force, ONS): The unemployment rate, i.e., the percentage of the economically active population aged 16+ who do not have a job and are looking for one (residency analysis). House income (ONS): measured by the Gross Disposable Household Income (GDHI) per head. Economic inactivity (Annual Population Survey/Labour Force, ONS) is the number of people not actively looking for a job.

Connect with the Authors

![]()

Nayara Albrecht is a computational political scientist and Assistant Professor at the Federal University for Latin American Integration (UNILA). She holds a PhD in Political Science (2019) and completed postdoctoral fellowships at Aston and Newcastle Universities. A former policymaker at Brazil’s Ministry of Culture, she has held academic and policy roles in Brazil and the UK, and currently chairs the International Political Science Association’s Research Committee on Politics and Business.

![]() : Nayara Albrecht

: Nayara Albrecht ![]() : https://nayalbrecht.github.io/

: https://nayalbrecht.github.io/

Blazej Jan Barski is a Geography and Politics graduate from Newcastle University and the founder of the Polish and Lithuanian Students Forum 2023. Having a background in geospatial engineering, he is due to start a PhD in Data Visualisation with the DIVERSE CDT, based at the University of Warwick and City, St. George’s University London. His primary research interest lies in the development of innovative geospatial data visualisation methods to support the analysis of the interplay between space and society.