A Snapshot of Transition Economies

Transition economies—namely Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kosovo, Moldova, Montenegro, North Macedonia, Serbia, and Ukraine—were socialist economies, characterised by weak institutions and inefficient markets. Since the early 1990s, these countries have transitioned from centrally planned to market economies, with EU membership as an ultimate goal. However, unlike the Central and Eastern European countries (CEEC) that joined the EU in and after 2004, these countries have made slower progress.

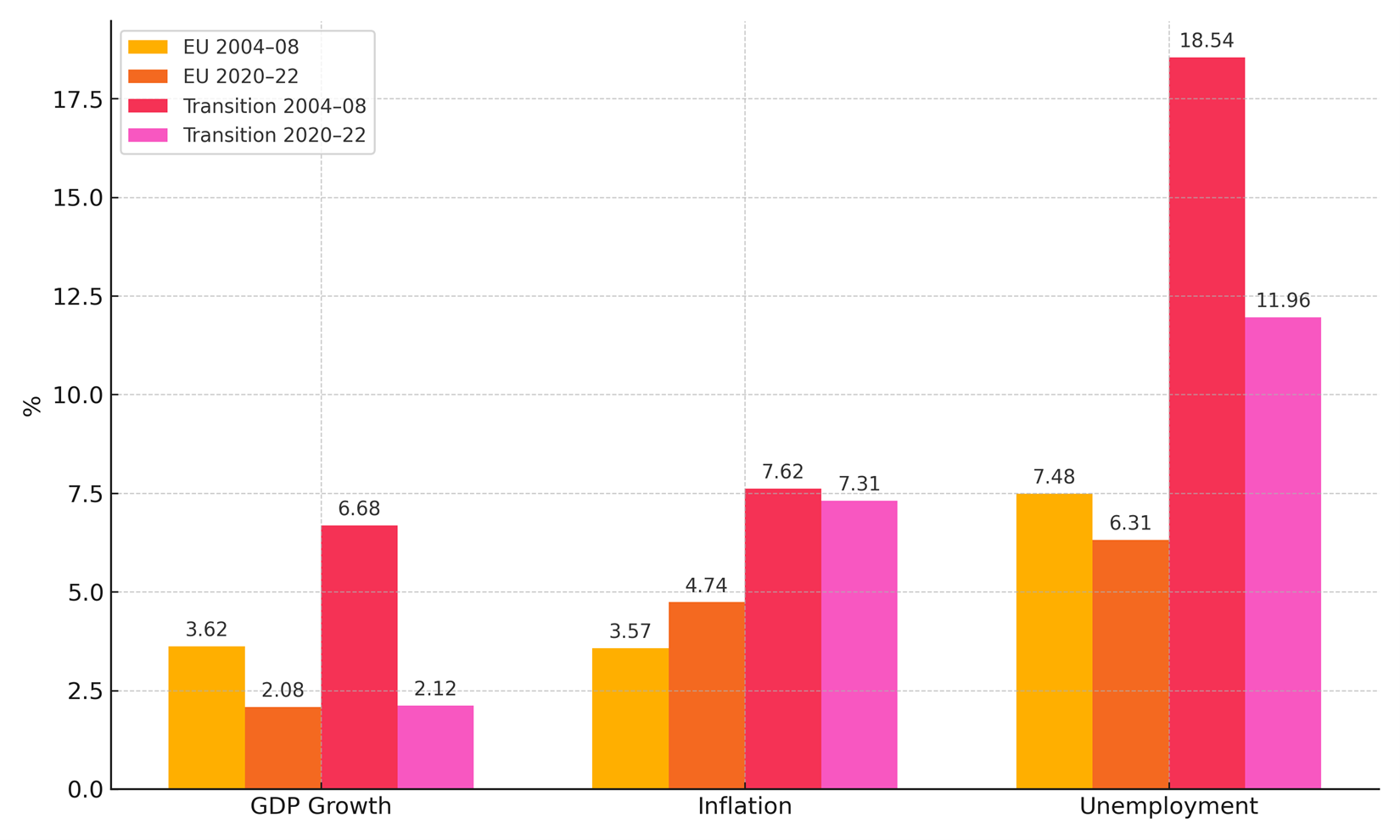

As shown in Figure 1, macroeconomic indicators—such as declining inflation and unemployment rates—suggest progress (e.g., Serbia’s inflation rate fell from 95.6% in the mid-1990s to 4.7% in 2024).

However, when viewed through the lens of integration maturity—a framework used to evaluate how ready a country is to join the EU based on factors like economic stability, competitiveness, and market functioning—a different picture emerges. The results are troubling: these countries lack the institutional foundations necessary for sustainable growth and deeper integration.

The Role of Institutions in Economic Growth

Institutions—the rules of the game in a society—are critical for development as they determine incentives for investment, innovation, and resource allocation. However, in many transition economies, weak property rights, limited judicial independence, and pervasive corruption continue to hinder sustainable growth. These institutional shortcomings discourage foreign direct investment (FDI) and hold back deeper, long-term changes needed to modernise the economy (see also: Acemoglu et al., 2005; Estrin & Uvalic, 2014; Šiljak & Nielsen, 2022).

While these countries have made some progress toward becoming competitive, functioning market economies, institutional factors play a less pronounced role in the current transition phase. This is not to say that institutions are irrelevant, but rather that their impact is impeded by structural inefficiencies and political unwillingness to reform.

Convergence Challenges

Convergence—a tendency of poorer countries to grow faster than richer ones and eventually catch up—of transition countries towards the EU has been slow. The countries do converge, but structural differences such as economic openness and institutional inefficiency continue to pose significant challenges. Periods of economic crisis, such as the recent episode of stagflation—a mix of slow growth and high inflation—caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, have made these weaknesses even more visible, showing how vulnerable these economies are to both global shocks and internal problems.

Growth Without Development?

One of the most striking observations is the phenomenon of “growth without development.” While GDP figures suggest progress, the underlying quality of this growth is questionable. Many transition economies remain dependent on low-value, labour-intensive exports and lack the industrial modernisation seen in earlier waves of EU enlargement. Their economies are service-based—a characteristic more typical of developed economies. As countries tend to grow at the highest rate during the industrialisation period—a step the current transition economies skipped—it is no wonder that they do not grow at a sufficient rate to achieve faster convergence. Recent experience in Hungary and Romania, where growth occurred alongside institutional backsliding, illustrates the risks of mistaking GDP performance for meaningful development.

What Can Be Done?

The road to convergence and EU accession requires comprehensive reforms. Transition countries must:

- Strengthen Institutions: Fighting corruption, ensuring independent courts, and protecting property rights are essential for building a stable business environment and attracting foreign investment.

- Diversify Economies: Investing in sectors such as technology and the manufacturing of high-value goods can increase production capacity, stimulate demand, and drive exports and GDP growth.

- Improve Infrastructure: Improving road quality will make trade easier, strengthen regional connections, help businesses grow, and attract foreign investment.

- Adopt EU Standards: Aligning domestic regulations with EU norms will ease the accession process and improve market efficiency.

- Invest in Human Capital: Education and training programs can develop a skilled labor force, boost productivity, create new jobs, and reduce migration.

A Cautious Optimism

Institutional reforms are crucial for successful economic transition and convergence. Although the path is challenging, the experience of CEEC demonstrates that progress is possible. For transition countries, the “advantage of backwardness” is still possible, but only with continuous efforts to build strong institutions and economies.

In conclusion, EU membership is not a right, but a privilege. Transition countries must understand that the process of integration requires both internal transformation and external alignment. With the right policies, they can unlock their potential and become prosperous and stable EU members.

Connect with the Author

Dženita Šiljak holds a PhD in Economics from the University of Sarajevo and is an associate fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies Kőszeg (iASK), Hungary. Her research focuses on economic convergence, institutional roles in EU integration, and populist policies.