The UK has historically failed to learn important lessons from European countries on spatial rebalancing. It has recently acknowledged the need for effective local institutions and a long-term national strategy, but its asymmetric approach is unlikely to reduce geographic inequality.

The failure of levelling up

When the previous UK government launched its levelling up agenda in 2019, its goal was quite clear: to tackle regional inequalities across the UK. The plan focused on boosting infrastructure, driving innovation, and developing skills in areas that were falling behind economically, alongside sub-national governance reforms across England. Despite the fanfare and detailed policy proposals in the 2022 White Paper, the project had achieved remarkably little by the time Labour took office in 2024, and what was achieved was patchy at best.

The failure of the project partly rested on its short timeframe (Diamond et al, 2024). But the main issues ran much deeper than this. The delivery mechanisms were fragmented, lacked strategic coherence, and simply were not robust enough (Hoole et al., 2023; Martin & Sunley, 2023; McCann, 2023). In our new paper, we identify a crucial lesson:

“if spatial inequality in productive capacity is tackled through a spatially unequal governance system, the outcome is likely to be a new pattern of spatial inequality, and not spatial rebalancing or anything resembling ‘levelling up’”.

Germany, Italy and France

The UK can draw valuable insights from other nations in Europe that have been more successful at tackling spatial inequality. Germany’s federal system stands out, with its 16 states wielding significant powers over education, economic development, and local government. The German constitution mandates collaboration between different levels of government, while long-term industrial strategies and major spending programmes ensure sustained progress (Raikes, 2022). The federal government actively redistributes tax revenues to address spatial disparities (Taylor et al., 2022).

Meanwhile, Italy and France have been on interesting journeys, from highly centralised systems toward more regional control through decisive steps on governance reform and spatial rebalancing. Italy adopted an asymmetric two-tier approach in 1948, granting special powers to ‘special statute’ regions (mainly in the north) while maintaining standard powers for ‘ordinary’ regions (mainly in the south) (Giovannini & Vampa, 2020). Then, in 2001, constitutional reform gave way to major changes in the distribution of powers (Palermo & Wilson, 2014), alongside an equalisation mechanism to help all regions provide uniform services despite varying tax revenue. In France, action was taken in the 1980s to transform how they govern by transferring significant powers to regional assemblies with immediate effect (Thoenig, 2005). Funding is equalised through national government grants as well as resource sharing within metropolitan areas (Taylor et al., 2022).

Identifying lessons

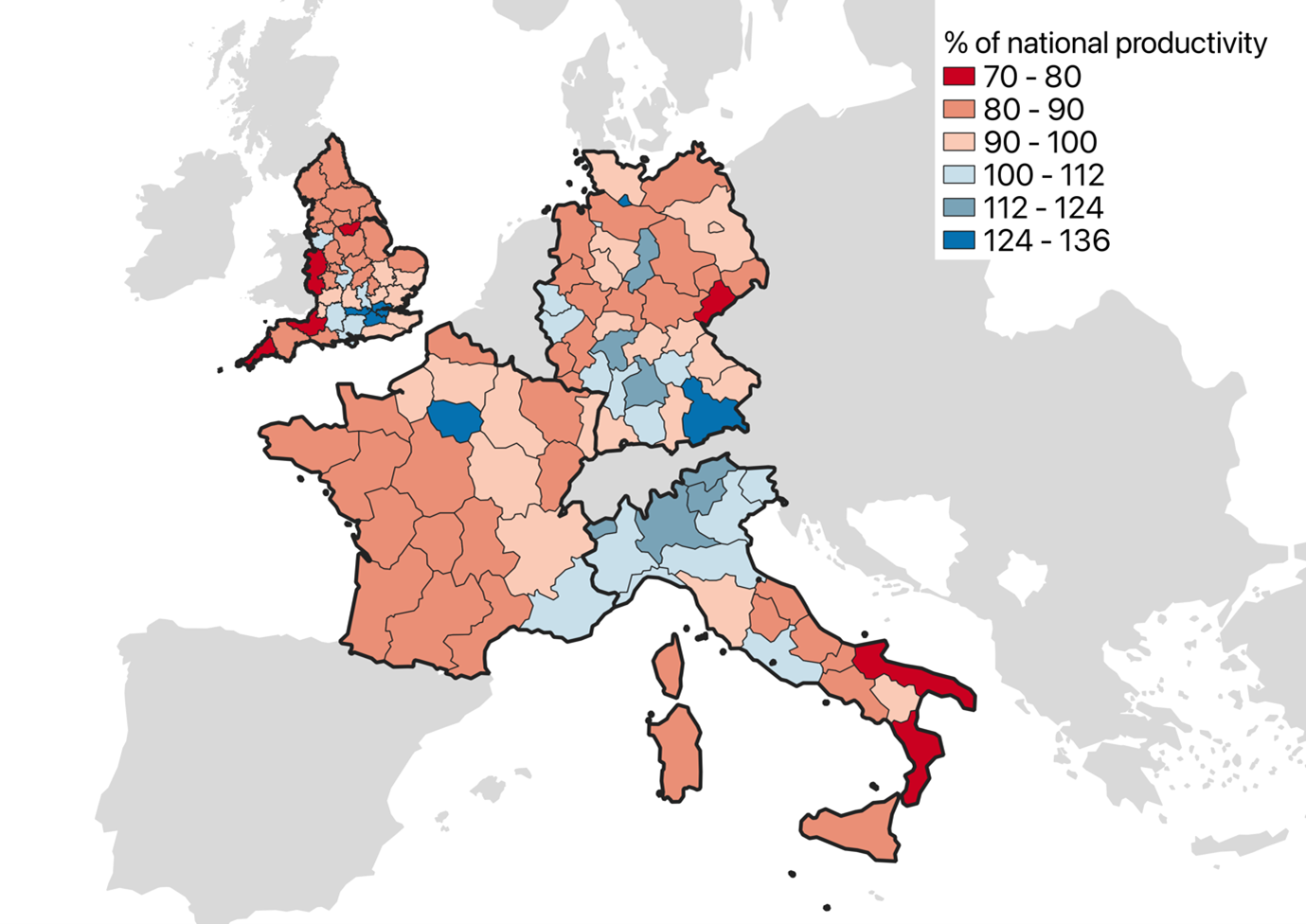

Despite progress, each of these countries still faces challenges, which are shown when we look at productivity (see Figure 1). Germany still struggles with East-West disparities, in Italy, the unequal legacy of asymmetric devolution persists with a North-South divide, and in France, rural areas continue to face disadvantages from its governance reforms.

Yet, countries with stronger institutionalised multi-level governance, like Germany, seem better equipped to address these imbalances than more centralised systems like the UK. Three key lessons stand out for the UK. First, progress requires a comprehensive national strategy, following Germany’s model of consistent industrial planning, rather than disconnected initiatives. Second, strong institutions and adequate funding are essential. And third, policy approaches must be tailored to local contexts – what drives growth in urban areas may not suit rural areas, as France’s experience demonstrates.

Is the UK learning these lessons?

The UK has historically failed on all three of these challenges. Its legacy of deeply entrenched economic inequality has persisted through successive short-lived and ineffective attempts at spatial rebalancing. Its changing patchwork of subnational institutions have been stripped of power and capacity, and systematically underfunded. And England’s asymmetric devolution gives some areas advantages over others, while its metro-centric spatial policy disadvantages towns, smaller cities, and rural areas. At the same time, the UK exhibits none of the success factors of these European comparators: its governance system lacks formal institutional structures, its industrial strategy is sporadic at best, there is no consistent agenda for spatial redistribution, there have been few decisive legislative moments with a lasting impact, and there appears to be no intention of transitioning away from asymmetric devolution.

New developments in the UK, including the English Devolution White Paper and the Industrial Strategy Green Paper published in late 2024, offer some potential to tackle these weaknesses. The re-establishment of a national industrial strategy over a 10-year timeframe provides a stable basis for thinking about long-term local economic development. The English devolution agenda also seeks to simplify, strengthen, and systematise England’s subnational government. However, what is missing from both the industrial strategy and the devolution agenda is a clear vision for tackling spatial inequality. Instead, the overriding focus on increasing national GDP is likely to see an ongoing focus on the biggest cities (Warner et al, 2024).

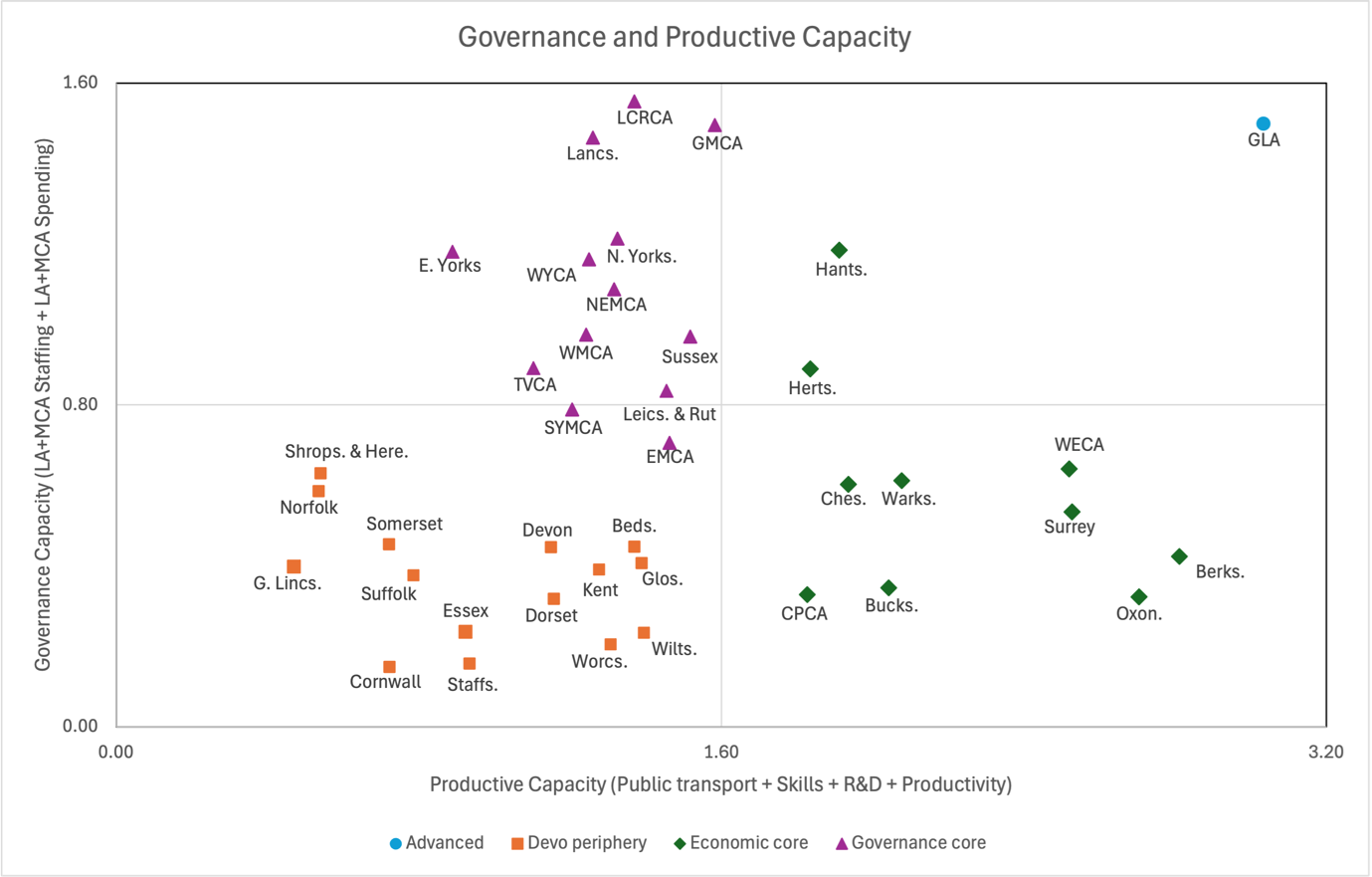

Our research shows that those places that are furthest behind on England’s devolution ladder are only likely to fall further behind (Hoole et al, 2023). In our most recent paper, we show that there is a significant cluster of places that are falling behind both politically and economically (see Figure 2 – Newman and Hoole, 2024).

These twin disadvantages are likely to reinforce each other, especially in the context of multi-speed devolution and metro-focused economic policy. One legacy of the levelling up agenda is the myth that it is possible to focus on the economic development and political empowerment of the major cities while assuming that smaller cities, towns, and rural areas will catch up. As the UK pursues a narrowly defined economic growth agenda, it is likely to drive a new era of spatial inequality. The government may ultimately find that it is a political backlash from the periphery that underscores the dangers of geographical inequality (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018).

Connect with the Authors

Charlotte Hoole is a Research Fellow at the City-Region Economic Development Institute, University of Birmingham. Her research broadly considers the geographical and political economy of local and regional development, governance and policy. Her current work focuses on English devolution and public funding allocation in the UK. Prior to this, she has worked on projects looking at the impact of governance structures in the formulation of place-based policies and central-local relations, and their role in shaping regional disparities.

![]() : Charlotte Hoole

: Charlotte Hoole ![]() : 0000-0002-6987-7797

: 0000-0002-6987-7797

Jack Newman’s research considers how decentralisation enables and constrains place-based policymaking and how it affects the spatial distribution of governance capacity and policy outcomes. In simple terms, if power moves downwards, is policymaking more effective, and are there fewer inequalities between places? In recent years, Jack’s research has focused on devolution and spatial policy in England, asking how the UK’s changing multi-level politics might enable more integrated, strategic, democratic, and preventative policymaking. Since January 2024, Jack has been a Research Fellow on the TRUUD project, focusing on how preventative health can be realised through devolution and cross-government working.