The blog below offers a reflexive, research-informed reflection on regional perception and spatial scale, grounded in lived experience in Australia. While it begins with a personal anecdote, it develops insights that align with broader discussions around borders, mobility, and comparative spatial experience. It contributes to ongoing conversations about how regions are perceived, experienced, and constructed in everyday life.

About two years ago, my family and I were enjoying sunny Sydney. While Sydney is a vibrant and iconic part of Australia, it does not represent all of Australia, and vice versa. This is clear to anyone who has lived in Australia or even Asia. However, for those of us from Europe, the sheer vastness of Australia might come as a surprise. Australia is the 6th largest country in the world and covers over 7.6 million square kilometres, fitting easily the whole EU with its 4.4 million. No wonder that the flight between two neighbouring cities in Australia is almost as long as flying from one country to another in Europe.

A snapshot of Australia!

Australia is also a global leader in science, technology, and innovation, consistently ranking high in international assessments. It holds the 1st position globally in terms of the quality of scientific research and is among the top countries for investment in research and development (R&D), with 2.1% of its GDP allocated to R&D. The space industry contributes $4.5 billion annually and supports over 10,000 jobs, and it is one of the hot spots for a world-class tech startup ecosystem. None of this happened by accident. However, Australia and the EU differ significantly, particularly in geography, identity, and how communities operate. Therefore, there are several lessons that the EU can take from this continent. Here are five lessons which I found interesting to share.

- International openness

Nearly half of Australians were either born overseas or have at least one parent born abroad. This creates not just diversity, but a national identity built around migration. People in Sydney live multiculturalism as a daily reality. Europe, too, is home to cosmopolitan hubs such as London, Paris, and Brussels. Yet while Australia frames openness as part of its competitive advantage, Europe often debates migration through the lens of crisis or burden-sharing. Theories of super-diversity (Vertovec, 2007) and urban cosmopolitanism remind us that integration is not just about managing flows but about embracing creativity and openness as assets. Europe could shift its narrative from defending against migration to leveraging it.

- Communities as a competitive advantage

One of the first things you notice when coming to Australia is the people – kind, welcoming, attentive and social. While stereotypes can be simplistic, community spirit is visible in local initiatives and social networks. Scholars like Putnam (2001) with social capital theories, urban governance and commons theories, have long argued that dense, trust-based ties strengthen societies. In Australia, distance and isolation seem to reinforce the value of community. That is how the community in Australia has become one of its competitive advantages, as highlighted by Jeffrey Bussgang and Jono Bacon, “When Community Becomes Your Competitive Advantage”. In Europe, strong community initiatives exist too, such as Barcelona’s urban commons, Dutch neighbourhood cooperatives, but they often operate in tension with complex bureaucracies. The contrast suggests Europe could learn from Australia’s lighter, community-driven models of governance, balancing formality with trust and participation.

- Local branding: “Australian Made” vs “Made in EU”

Walk into any Australian store, and one can see the green-and-gold kangaroo: the “Australian Made” logo. It signals authenticity, quality, and pride. Consumer preference for Australian-made products is extremely high. A 2020 Roy Morgan survey found

- 93% of Australians were more likely to purchase products labelled “Australian Made”;

- 97% Consumers associate it with supporting local jobs;

- 95% associate it with safety and high-quality products;

- and 89% associate it with ethical labour practices.

This is recognition and trust that make the ” Australian Made” brand a powerful tool for businesses globally.

Europe also has long traditions of protecting origin, through geographical indications (GIs) for e.g. wines, cheeses, or regional products, but attempts to create a unified “Made in EU” brand have failed (“Made in EU” was proposed by the European Commission in 2014 but did not make it to the EU legislation.)

The contrast is clear: Australia built a single, recognisable national label, while Europe remains fragmented. Theories of regional development and endogenous growth (Johansson, Karlsson and Stough, 2001) highlight how strong local brands can drive long-term economic growth and resilience. A European equivalent could enhance consumer trust and identity while supporting competitiveness.

- Public good practices

In Australia, non-excludable and non-rivalrous goods like public toilets, drinking water taps, and museums are free. This reflects the nation’s commitment to cultural enrichment, education, public health, and social equity, ensuring that essential services and cultural experiences are within reach for everyone. Europe also provides public goods, but unevenly; some museums are free, while others are costly; access to safe water is standard, but not always celebrated as a right. Europe’s practice suggests that while the principles exist, the implementation varies widely. In Europe, countries such as the UK, Sweden, and Germany offer varying degrees of free access to museums, while water taps and libraries in the Netherlands, France, and Spain are often supported by public funding.

However, the practice shows that symbolic policies, such as visibly free public amenities, can strengthen equity, trust, and be more aligned with keeping Europe united.

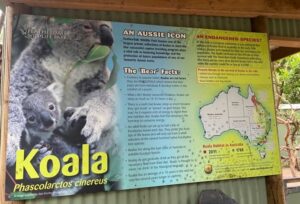

- Environment and sustainability as initiatives and policy

Australia’s biodiversity, with over 2,000 native plant species thriving in its diverse landscapes, from coastal cliffs to lush national parks, is not just a resource; it is central to its identity. This nature is highly preserved by people and also by a large number of organisations, NGOs and initiatives, e.g., the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC), Nature Conservation, Tasmanian Land Conservancy, and many more. This happens while there are quite a few large country-wide regulations for environmental protection and nature preservation. Meanwhile, Europe is ambitious in its climate and nature preservation efforts, as demonstrated by the European Green Deal, the Fit for 55 Package, the Biodiversity Strategy, and the EU Renewable Energy Directive. However, the EU can scale more with stronger citizen, industry and bottom-up engagement. This would also align with the environmental governance theory, which emphasises multi-level coordination, regulation, and stakeholder engagement to collectively address ecological challenges.

Conclusion:

Lessons to drive competitiveness

Australia and Europe share many common goals —innovation, sustainability, and openness—but approach them differently. Australia often frames diversity, community, and bottom-up initiatives as sources of strength, while Europe tends to approach them from a high-level governance perspective, treating some approaches as challenges.

What approach should the EU take?

The EU can blend the best of the two models to strengthen its competitiveness. Take the lessons from Australia and tailor them to the EU context to make a stronger impact.

One way to approach this is to develop joint projects, where the experience from Down Under is shared with Europe and vice versa. In 2024, the EU and Australia will have already celebrated 30 years of collaboration, reaffirming their commitment to advancing science and technology. Bilateral research collaboration priorities are set and monitored at Australia-EU Joint Science and Technology Cooperation Committee (JSTCC) meetings. The EU-Australia partnership in science and innovation offers several advantages, including enhanced research capabilities, shared expertise, and coordinated responses to global challenges such as climate change and health crises. By leveraging complementary strengths and fostering mutual benefits, this collaboration contributes to the advancement of sustainable development and innovation on both sides.

Mutually interested areas of cooperation are health, food and natural resources, energy and transport, space, research infrastructures and researchers’ mobility.

Let’s leverage this partnership to create a win-win future! Welcome to reach out if you have any thoughts or suggestions for joint projects or research cooperation.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Connect with the Author

Anastasiia Konstantynova is a principal consultant at Technopolis Group (Amsterdam).