The first signs of a slowdown in residential address changing were identified towards the end of the last century, starting in the USA, as is so often the case with social trends and then being found to be particularly marked across the rest of the New World. But other countries, including the UK, have not been immune to this tendency, leading to studies of its scale and nature and concerns about its consequences for housing, jobs and society.

My previous research with Ian Shuttleworth (2016) (QUB) using the Office for National Statistics Longitudinal Study (ONS-LS) showed that for England & Wales, more than half (55%) of the residents in the 2001 Census and identified again in the 2011 Census were still living at the same address. This was a substantial increase from the overall proportion of 45% who did not change address between the 1971 and 1981 Censuses, with older people and shorter-distance moving being the most notable contributors to what Tom Cooke (2011) has labelled “secular rootedness”.

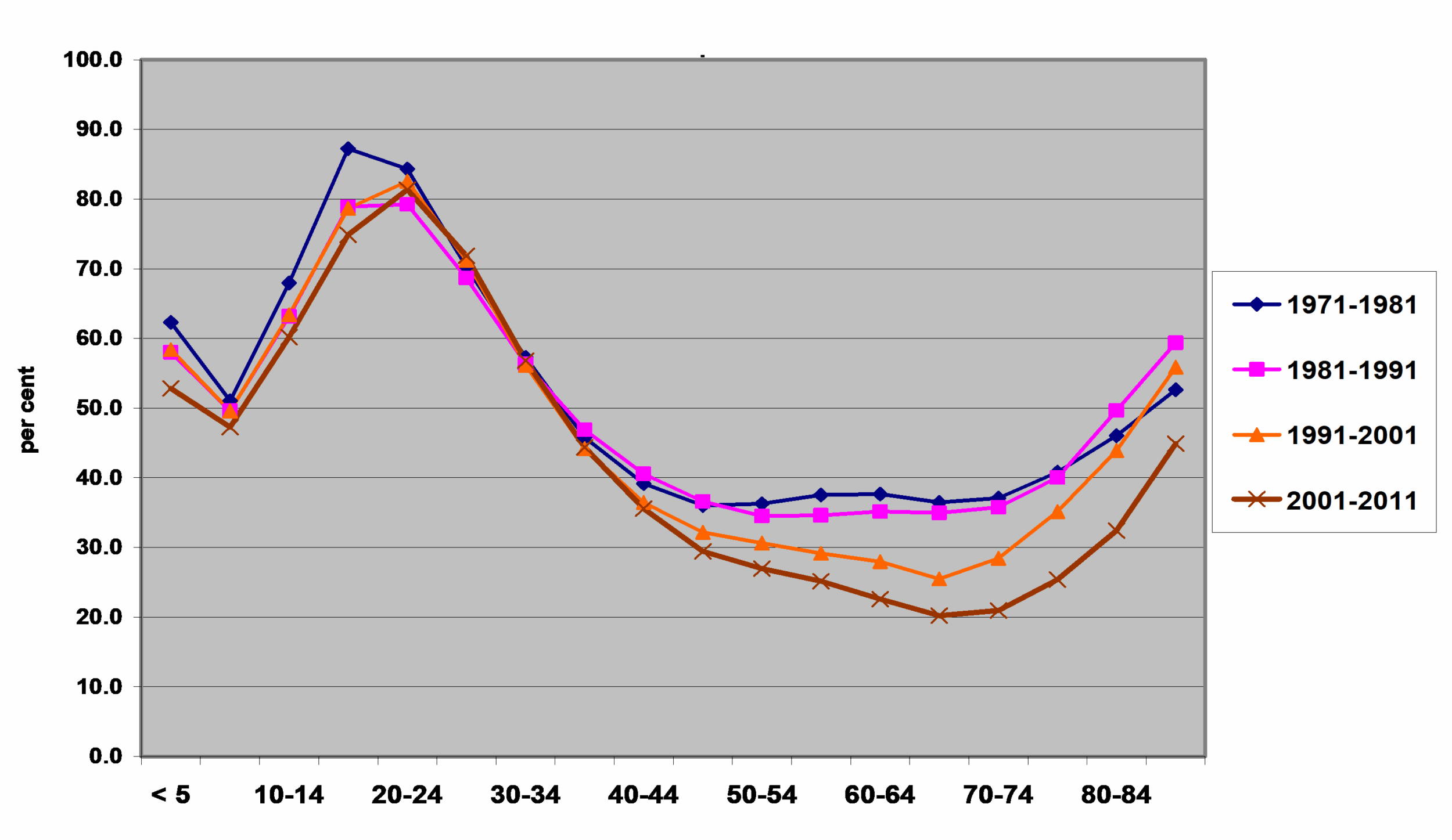

This chart shows the clear and progressive clear drop in the proportion of people changing address in England and Wales between censuses, especially for moves of less than 10km.

This chart highlights the steep drop in intercensal residential mobility among older adults, with the proportion of movers among those in their 60s almost halving between the 1970s and the 2000s.

Once the 2021 Census data are available from the ONS-LS, it will be interesting to see whether this downward trend in 10-year address changing rates has continued since 2011. But the MHCLG’s English Housing Survey (EHS) – albeit with a much smaller sample – suggests a continuing fall in rates, with the proportion of households resident at their current address for less than 12 months down from 9.2% in 2011 to 7.9% in 2022.

Why are we moving less often?

For older adults, less movement is often a positive outcome. Improved health in later life, the accumulation of untaxed housing wealth, the possibility of using equity release to maintain incomes, keeping local ties and having space for visiting family all play a role. Yet many retirees face genuine barriers to moving—transaction costs like stamp duty, emotional strain, and a lack of appealing downsizing options all contribute.

But for younger people and society as a whole, the picture is far less rosy. True, longer-distance migration rates have kept up, but this is mainly because of the rising participation in higher education and the continuing popularity of going away to university. For other school leavers and those from less wealthy families, however, the prospects for setting up home independently are considerably poorer than they used to be. This is reflected in the rise in proportion of 25-34-year-olds still living with their parents, now 1 in 5 according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (2025).

Labour Mobility at Risk

These changes seem to be altering the role of the private rented sector (PRS) from one of high turnover, providing fairly temporary accommodation for young adults saving to buy or waiting for a council house, to now providing a more permanent home. According to the EHS, the proportion of private tenants living at their current address for less than a year has halved from 40% to 20% since the early 2000s, while the share aged 16-29 has dropped from 36% to barely a quarter now with many of these likely to be students away at university.

A key issue here is that historically, the PRS has played an important role in facilitating labour mobility. Young people moved to job-rich regions like the South East, using rental housing as a temporary base. But now it is much more difficult to make such a move without financial backing or a university degree. As a result, employers in high-demand regions struggle to recruit, talent in left-behind areas remains underutilised, and regional inequality in skills and opportunities grows. More generally, reduced labour mobility risks a less dynamic economy and lower productivity, and there are wider social and health consequences.

The Fundamental Problem

What Rory Coulter calls our “increasingly dysfunctional housing system” poses a huge policy challenge. According to the Centre for Cities (2023), the chief culprit is a fundamental shortage of housing: if we had been adding to the stock at the rate that other countries in Western Europe have been since 1955, even after allowing for differences in growth rate we would have 4.3 million more homes than we do now.

At the heart of this problem lies a planning system established in the late 1940s when there was net emigration and the population was virtually static – a far cry from even the 1960s (when the problems were already being noted by Peter Hall (1973) and colleagues in their magisterial analysis The Containment of Urban England) but much more so since the 1990s with high levels of immigration from overseas.

What To Do About It

The government’s pledge to build 1.5 million new homes by 2029 is a start—but not nearly enough. Tackling falling mobility requires systemic reform, as advocated. Suggestions from the literature include:

1. Grow the Housing Stock Faster: Build much more housing for both purchase and social renting.

2. Make Downsizing More Attractive: Build more age-appropriate housing, reform stamp duty, and provide moving support.

3. Revamp Private Renting: Improve tenant protections, affordability, and quality.

4. Liberalise Planning: Explore further options, including freeing up land around railway stations in the Green Belt for development.

5. Link Housing and Jobs: Support relocation for work, invest in transport links, and align housing with economic planning.

6. Regenerate Left-Behind Areas: Boost investment, services, and infrastructure to reduce the need for relocation in the first place.

Conclusion: Rootedness with Consequences

Staying put might feel comfortable for individuals, but collectively, it creates friction in the housing markets, reduces labour mobility, and hinders economic progress. The UK needs a policy reset to balance personal stability with societal dynamism. Understanding and addressing why people don’t move is just as important as deciding where to build next.

This blog is a summary of key points by Tony Champion (Newcastle University ), a presentation made to the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government about the declining frequency of people moving home, and its discussion on its impact on housing and labour markets and the nation more generally.

Slides for Tony Champion’s presentation to the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government can be viewed here.

More about Tony’s work: https://www.ncl.ac.uk/curds/contact-us/people/profile/tonychampion.html

Connect with the Author

Tony Champion is Emeritus Professor of Population Geography at Newcastle University. His research interests include migration and its role in counter-urbanisation. He chaired the IBG Working Group on Migration in Britain, which led to Migration Processes and Patterns, and the IUSSP Working Group on Urbanisation, which led to New Forms of Urbanisation: Beyond the Urban-Rural Dichotomy. He is the past President of the British Society for Population Studies. His most recent work is on HE-related migration and its effect on concentrating young talent in large cities.