Nigeria’s business environment has been defined by overlapping crises—economic shocks, political instability, and community-level disruptions. For example, in 2015, Nigeria entered a prolonged downturn, largely driven by plummeting oil prices and production cuts. Between 2000 and 2012, crude oil accounted for 98% of the country’s export revenue and 85% of federal government revenue, yet its price fell from over $100 in the early 2010s to $50 per barrel in 2015 and $40 in 2016 (Omitogun et al., 2018). This external shock was followed by a period of stagnation and led to Nigeria becoming the “world’s poverty capital” by 2018, overtaking India (Elomien et al., 2022).

But economic decline wasn’t the only challenge. The country simultaneously endured massive insecurity—from Boko Haram insurgencies (Lenshie et al., 2024) to herdsmen-farmer conflicts (Nnaji et al., 2022). These not only destabilised communities but also displaced hundreds of thousands, interrupting local economies and labour markets, and creating food insecurity. Inflation and unemployment surged, with the latter hitting 33% by the end of 2020 (NBS, 2021). Against this backdrop, businesses—especially family-run non-farm enterprises (NFEs)—found themselves exposed to price shocks and weak consumer demand.

What makes this especially concerning is the systemic vulnerability of Nigerian enterprises. In a context where formal safety nets are limited, firms often rely on family labour and community-based support. Yet, as Banerjee and Duflo (2011) highlight, informal support systems are not always sufficient when shocks become widespread. Localised or individual shocks—like illness or theft—can sometimes be absorbed by family support structures. But broader economic shocks, such as inflation or food price surges, ripple across entire regions and exhaust these informal mechanisms.

In this setting, resilience becomes not just a buzzword but a necessity. Common-pool resources, bound by strong norms of cooperation, can buffer shocks through collective action. During crises, the strength of community ties, shared infrastructure, and mutual accountability can mean the difference between NFE collapse and survival.

As we argue in Estrin et al. (2025a), the historical tradition of cousin/consanguineous marriage creates dense social networks that facilitate resource pooling, cooperation, and informal social insurance—critical tools for survival amid systemic shocks. Our argument and empirical evidence point to positive aspects of endogamy tradition, which should be seen alongside its negative influences, e.g. on innovation, identified in the literature (Henrich, 2020; Todd, 1985).

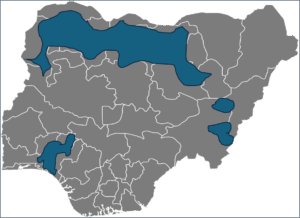

Note: Map of Nigeria showing regions of historical cousin marriage tradition preference in blue.

African thinkers like Chinua Achebe (1958) and Ayi Kwei Armah (1988) have long emphasised the resilience rooted in African communalism. Achebe, in Things Fall Apart, subtly portrays how deeply communities are interwoven, and how crises challenge not just individuals but entire social fabrics. Similarly, Ayi Kwei Armah’s “The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born” shows how the moral decay of governance systems puts the burden of survival on the ordinary citizen and family. These insights still echo the experience of Nigerian NFEs today—navigating shocks not in isolation, but within fragile ecosystems. Crises will come and go, but only resilient firms rooted in robust support systems, both formal and informal, will thrive.

Nigerian NFEs are frequently exposed to severe crises—both macroeconomic and regional—that threaten their viability. In such fragile environments, the concepts of resilience and robustness—a firm’s ability to withstand and recover from crises—are not only important but vital. Our research on Nigerian NFEs demonstrates that resilience is not determined solely by firm-level attributes like capital or managerial education (Estrin et al., 2025a). Resilience is also significantly shaped by informal social institutions, including local kinship structures rooted in the historical tradition of cousin marriage.

The historical tradition of cousin/consanguineous marriage, often debated for its social implications (Henrich, 2020), in this case serves as a powerful mechanism of economic resilience by creating dense, overlapping networks of obligations. These networks promote trust, reciprocity, and mutual aid within the community. Thus, the tradition does not merely reflect cultural identity; it facilitates collective resilience. As we argue (Estrin et al., 2025a), in the absence of formal safety nets, these kin-based networks still operate as a decentralised form of crisis response in contemporary Nigeria.

But at the same time, there are trade-offs to consider when examining the benefits of such traditions. While the historical tradition of cousin marriage may enhance resilience by strengthening kin-based social support and informal finance during economic crises, it may simultaneously constrain other important business outcomes—particularly innovation and growth (Henrich, 2020). Dense kinship networks often foster conformity, trust, and reciprocity, but these same qualities can discourage openness to new ideas, reduce diversity of perspectives, and limit interactions with the broader market or external actors. Innovation frequently depends on weak ties—connections outside one’s immediate circle—that bring in novel information and alternative approaches. In contrast, endogamous communities may reinforce insularity, leading to path dependence and reduced adaptability in dynamic, competitive markets.

Furthermore, enterprises embedded in closely knit kinship networks may face social pressure to hire family members, even when better-qualified candidates exist outside the group (Estrin, 2025b). This limits meritocratic decision-making and can stifle organisational learning. Thus, while endogamy offers protective advantages during downturns, it can hinder longer-term transformation, competitiveness, and integration into broader economic systems. Policymakers and development practitioners should be mindful of these trade-offs, promoting resilience without sacrificing the openness and diversity that foster innovation and sustainable growth in the long run.

Offline References

- Armah, A. K. (1968). The beautyful ones are not yet born. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Banerjee, A., & Duflo, E. (2011). Poor Economics. New York, NY: PublicAffairs.

- Achebe, C. (1958). Things fall apart. London: Heinemann.

- Henrich, J. (2020). The WEIRDest people in the world: How the West became psychologically peculiar and particularly prosperous. London: Penguin.

- Todd, E. (1985). Explanation of Ideology: Family Structures and Social Systems. Oxford: Blackwell.

Connect with the Author

Tolu Olarewaju is a lecturer in Management at Keele University. Tolu’s present research interests centre on entrepreneurship, transparency, international business, business economics and poverty reduction. Tolu is a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy and a Fellow of the Chartered Management Institute. Tolu also has industry experience, both as an entrepreneur and a banker in Nigeria.

![]() :Tolu Olarewaju

:Tolu Olarewaju ![]() : ToluOlarewaju

: ToluOlarewaju

Saul Estrin, a Professor of Managerial Economics, is based at LSE and formerly at LBS. He has published extensively in scholarly journals about emerging economies, entrepreneurship and foreign direct investment. He is a Fellow of the British Academy.

Tomasz Mickiewicz is a senior fellow of the Regional Studies Association, a former editor of the Regional Studies journal, and a current editor of Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. He works as a professor of economics at Aston University (Birmingham) and is a member of its Centre for Business Performance. He is also a member of the UK team of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor and an honorary senior research fellow at University College London. He publishes on regional economics, institutional economics, and entrepreneurship.