Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s fastest-growing megacities, with over 15 million inhabitants according to the latest census (The World Bank Group, 2018). According to the CAHF (2018), the city’s rapid and often unregulated expansion has given rise to what urbanists call chaotic settlements, particularly on the peripheries. Yet, these patterns of development reflect a return to traditional Bantu systems of organisation, emphasising self-built housing, communal structures, and agrarian lifestyles while still bearing the imprint of colonial legacies in the built environment.

One such area is Mont Ngafula Commune, located in western Kinshasa. According to Mutombo (2014), historically, Mont Ngafula is one of the oldest Belgian settlements and had mainly remained underdeveloped until the late 1990s, when it transitioned from a rural village to an agro-pastoral zone tasked with feeding Kinshasa’s urban population. In 1968, it was designated as an urban commune under Mobutu’s Presidency (Luzoladio, 2020).

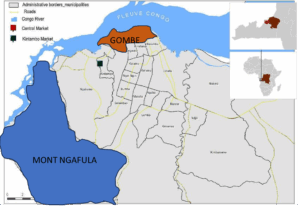

Covering 456.36 Km², three times the size of Brussels, it is the largest yet least densely (Mutombo, 2014) populated of Kinshasa’s urban communes, with only 15.65 people per km², compared to 174.25 in other peripheries and 1,154.8 citywide. Between 2013 and 2017, its population grew from below 500,000 to over 714074, representing a 10% growth rate, the highest in the city (Japanese International Cooperation Agency, 2019). The commune is subdivided into quarters, shares borders with five other communes and provides access to both the central Gombe district in the East and Kongo Central Province in the South, making it strategically significant. This position has made Mont Ngafula a very attractive land for urban expansion with new housing development.

Housing Development and the Legacy of Colonial Planning

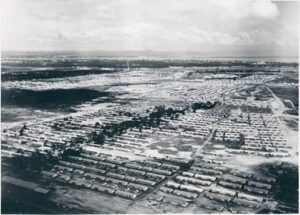

During colonial rule, the Belgians imposed a rigid urban design based on Western grid plans, featuring wide, straight streets and modular housing units that did not reflect the lifestyles of local communities. These were often small, barrack-like houses aligned along streets in “indigenous cities” or cités indigènes. However, in zones under customary chiefs, settlement followed traditional forms, promoting self-built homes using local materials, open plots without fences, and organic paths that often crossed through private spaces. And through my study of self-built housing in a peripheral commune, I show how the spatial imaginary created by Belgian urban planners has been reshaped by customary practices of place-making.

Following independence, a significant increase in the indigenous urban population led to the emergence of new settlements developed by locals with no formal training in urban planning. The birth of quarters with Ndaku ya Sika (new homes) featured large self-built homes on open plots, echoing traditional settlement models (Nzuzi, 2020). With the sudden departure of the colonial administration in 1960, governance structures collapsed, and urban planning fell into the hands of inexperienced elites and customary chiefs. Hesselbein (2007) and Booth (2015) argued that this abrupt transition left the city without organised management. Land was distributed informally, often through political patronage and ethnic ties, exacerbating disorganisation in a town without an updated Master Plan.

Today, over 80% of Kinshasa’s built environment, particularly in peripheral communes such as Mont Ngafula, consists of self-built housing (Mutombo, 2015). These homes are often constructed in hazardous areas, such as on steep slopes, marshes, or former agricultural lands, due to a lack of regulation. The absence of government oversight has allowed customary chiefs to distribute informally. As a result, many neighbourhoods carry the names of local chiefs, such as Ngafula.

Despite limited access to basic infrastructures such as water, electricity, and roads, residents continue to settle in these areas as land ownership remains a marker of dignity and identity within Bantu society (Batubenga R. et al., 2021). The existence of rural customs in urban settings illustrates a unique convergence of tradition and modernity, as well as a desire to reflect traditional values in the city’s landscape and housing.

For example, Kimbuala, the area of study, one of Mont Ngafula’s 20 quarters, epitomises this pattern. Initially, the agrarian land owned by the customary authorities began to transform into a residential zone in the early 1990s, around the Don Bosco school and nearby monastery. The area continues to reflect rural traditions, such as farming and livestock rearing, even within an urban environment.

Conclusion

The development of Mont Ngafula and its quarters, like Kimbuala, demonstrates how Kinshasa’s peripheral expansion is both a response to and a reflection of indigenous consciousness. While colonial planning legacies remain visible, they have been adapted or outright replaced by customary practices rooted in traditional Bantu land tenure and community living (Murray J.S., 1970). This blend of rural traditions and urban adaptation challenges conventional models of city-making, highlighting the need to integrate traditional authorities into formal urban planning systems and the customary leadership’s crucial role in shaping inclusive, functional, and culturally relevant urban environments in the Kinshasa periphery.

Connect with the Author

Alex Nyembo Kalenga is a Ph.D. Scholar at Anant National University, focusing on the sustainability of self-built homes in Kinshasa, DR Congo. He served as a Professor at GD Goenka University from January 2022 to May 2024 and as a Visiting Lecturer in the Architecture Department at Nouveaux Horizons University in DR Congo. Previously, Alex served as a Course Leader at Pearl Academy in India. He holds a Master’s in Renewable Energy and Architecture from The University of Nottingham, an Advanced PG Diploma from TERI University, and a bachelor’s degree in Architecture from the School of Planning and Architecture in New Delhi.