Logistics warehouses, hubs, and freight villages are spreading rapidly in European metropolitan peripheral areas. They sustain local economies, but as an adverse effect, they increase traffic, pollution, land consumption, and, sometimes, migrant workers’ exploitation. Policy and planning by public administrators and decisions by private logistics stakeholders have essential and controversial roles in logistics development, which must be unpacked.

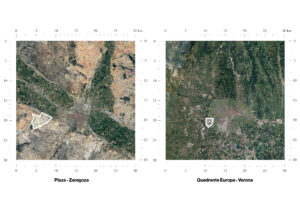

Figure 1 – Satellite images from Google Maps, elaboration by the authors

“Freight Villages” and Place

The flow of goods is mobile. However, to run, it needs sites embedded in physical space. Among these sites, freight villages play a crucial function. By ‘freight villages,’ we mean big logistics platforms where goods move from trains to trucks and vice versa; while working on this type of sites within the complex European geographies of logistics, we have observed that national and EU policies consider them from a rather technocratic and sectoral perspective (i.e., European Commission 2023, Italian NRRP 2024, Spanish NRRP 2024). Indeed, institutional discourses describe freight villages as nodes in a global flow network, as intermodal hubs where goods change means of transport, as ‘complex machines’ to be made more efficient and sustainable, as companies to support against international competition, as triggers for regional growth, as opportunities for new jobs, and as business matters for real estate. Hardly any policies consider freight villages as places.

We suggest considering freight villages as places can be relevant for the present and future of the city-regions they are part of. On the one hand, these logistics platforms are places per se. Usually, they seal a vast portion of their soil with warehouses and surfaces of asphalt and concrete, and they mitigate their impact by creating green buffer zones around them. Being places, freight villages are ‘inhabited’ by thousands of workers every day (and every night), and thus, their spatial quality impacts the quality of life of their ‘dwellers.’ On the other hand, these are places related to other places: They are in (peaceful or conflicting) relationships with their close context, the landscapes they contribute to shape and reshape, their city-regions, and beyond (Beyers & Fowler 2012, Hesse 2020, Raimbault 2022). In our ongoing research, we look at freight villages as places through the cases of Quadrante Europa in Verona (Italy) and Plaza in Zaragoza (Spain).

Quadrante Europa

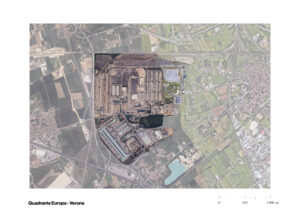

In European rankings (GVZ 2020), Quadrante Europa in Verona contends the title of the continent’s best-performing freight village with Cargo Distribution Centre in Bremen, Germany. Quadrante Europa has a strategic location in the heart of an international highway and railway hub connecting east-west (to and from France and Spain on one side and Eastern European countries on the other side) and north-south (from or going to central-northern Europe via the Brenner Pass).

With an area of about 250 hectares (618 acres) and a planned expansion of another 170 hectares (420 acres), Quadrante Europa is larger than the entire historic centre of Verona. Today, it is home to around 120 companies, employing 13,000 people (Verona has a population of 260,000).

Local governance discourses consider Quadrante Europa the largest island in Verona’s production archipelago. However, looking wider, we can observe the ongoing mushrooming of logistical settlements along the whole Brenner highway, especially between Mantua and Verona. For example, in recent years, logistical warehouses of Honda (serving the whole of Southern Europe), Zalando (1,700 employees), and Adidas (due to open in 2024 with around 700 employees), among others, opened along this route. Further, Quadrante Europa is not only the most important island of a ‘logistics city-region’ between Verona and Mantua, but it also dwells in the context of a progressive ‘logistical colonisation’ of Northern Italy.

Figure 2 – Satellite image from Google Maps, elaboration by the authors

Plaza

The title of Europe’s largest freight village belongs to Plaza, an acronym for Plataforma Logística de Zaragoza. Plaza covers an area of approximately 1,350 hectares (3,335 acres) and plans to expand by another 200 hectares (500 acres) in the coming years. About 15,000 people work there, spread over more than 500 companies (including Inditex, Amazon, Decathlon). Plaza is directly connected to Zaragoza Airport, a dedicated railway terminal, and three of the main highways in the centre and north of the Iberian Peninsula. Unlike the case of Quadrante Europa, Plaza has been used by the Aragonese autonomous community (the administrative region of which Zaragoza is part) as a starting point to ‘sell’ the entire region as a logistics hub (Hesse 2015): Since 2017 Aragón Plataforma Logística is a network that associate Plaza with four other smaller logistics platforms with the aim of making Aragon the first logistics region in Spain, to extend the logistics wealth of Plaza to the entire autonomous community.

Figure 3 – Satellite image from Google Maps, elaboration by the authors

What about places?

What will become of these freight villages? They could remain as they are, expand, be transformed, shrunk, or even close and be abandoned. In this last case, will we keep them as ‘toxic heritage’ (Kryder-Reid & May 2024)? We cannot predict what the future of these platforms will be. However, what we can do (what regional policymakers and stakeholders can do) is to start seeing freight villages not only as functional points but as places that have mutual influences with their contexts at different scales. Keeping in mind this spatial perspective, we think, can support in preparing freight villages for different possible futures and thus can also influence the future of their city-regions.

Funding

This blog post is related to the MeRSA Grant 2022 “Logistics city-regions in transition. New spatial imaginary?” (PI: Simonetta Armondi)

Simonetta Armondi, Associate Professor, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, Italy

Beatrice Galimberti, Research Fellow, Department of Architecture and Urban Studies, Politecnico di Milano, Italy

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.