The advent of technology and concomitant digitalisation has unleashed new business models and working arrangements in urban centres. The gig and platform economy are at the heart of this structural transformation of jobs, disrupting sectors like ride-hailing transport services, education, home services, food delivery, retail, logistics and so on. I refer to this as ‘Digihenheimer’- a counter phenomenon to regular paid jobs/full time jobs.

What is a Gig Worker?

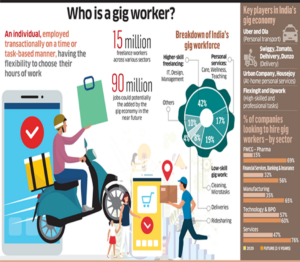

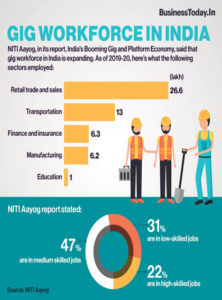

In the Niti Aayog report, gig workers are defined as those engaged in livelihoods outside the traditional employer-employee arrangement. They can be broadly classified into platform and non-platform-based workers. Platform workers are individuals whose work is based on online software apps or digital platforms. While non-platform gig workers are generally casual wage workers and own-account workers in the conventional sectors, working part-time or full time. Gig jobs are flexible, on a temporary basis, and mostly created by the digital networks. An official estimate of 200,000 gig-workers, in Dunzo, Swiggy, Zomato, Blinkit, are employed in Bengaluru alone and this number is increasing each day. According to the report by NITI Aayog and IBEF, the gig workforce in India is 7.7 million and is expected to expand to 2.35 crore (23.5 million) workers by 2029-30. India to have 1billion smartphone users by 2026. In another estimate, India is likely to have 350 million gig jobs (23%) by 2025, presenting a huge opportunity for job seekers to capitalise and adapt to the changing work dynamics. The report by ASSOCHAM reveals that the size of the gig economy is estimated to grow at a CAGR of 17%, and will hit a volume of $455 billion by 2023.

The gig economy encompasses freelancers, online platform workers, self-employed, on-call workers, and other temporary contractual workers. Despite the fact that non-platform gig workers typically earn casual wages and work on their own accounts in traditional industries, yet continue as part-time gig employees. Gig employment is flexible, transient, and primarily involve building digital networks. In Bengaluru alone, there are reportedly 200,000 gig laborers hired by Dunzo, Swiggy, Zomato, and Blinkit, and this number is rising daily.

Source: Deccan Herald (2021)

These new business models and working arrangements have been ushered in by the development of technology and the ensuing digitalization in metropolitan cities. The gig and platform economies, which have disrupted industries like retail, professional services, home services, and ride-hailing transportation, are at the center of this structural transformation which is fundamental of the labor market. I call this the “Digihenheimer” phenomena, which is the opposite of traditional, paid employment.

Key Drivers of Gig Work

Economic liberalization and the digital revolution, the rise of mobile and internet usage, and the expansion of e-commerce (retail) are some of the major forces behind the establishment of the gig economy in India. Due to the unorthodox job opportunities (without having to wait for traditional or conventional forms of employment), growth opportunities, flexibility and better work-life balance, as well as the option to not have a college degree, millennials are now choosing gig-jobs and freelancing opportunities over the traditional work culture. For non-core activities (engineering, product, data science, and machine learning), the start-up ecosystem in India employs contract-based freelancers. While MNCs encourage employment options for specialized projects, which notably contributes to India’s gig economy.

Source: Aayog (2021)

‘Vulnerability’ is a Major Issue

Although there are many different types of digital/app-based jobs, they all share the same existential issues of precarity, instability, unemployment, and informal employment circumstances within “formal” sector organizations. Due to contractual obligations, there are no workplace entitlements.

There has not been a shift in the manufacturing sector to the service sector in Indian cities, which would have increased work chances for young people. To put it another way, gig economy employees (from companies like Uber, Ola, Swiggy, Zomato, Blinkit, Zepto, etc.) typically lack social security (such as an EPF or pension), exposure to expertise, and little to no negotiating power. This has an impact on their pay or working conditions. It was discovered during the Pilot (May & June 2023) that there is a sizable difference in compensation before and after the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, those who were working before the outbreak of pandemic were making between Rs 12,000 and Rs 15,000 per week but after the outbreak are now making between Rs 5,000 and Rs 7,000 which is almost half of the payment. Following the pandemic, it is reported that the incentive amount was significantly reduced, which had an impact on their average monthly income.

Social inclusion in the platform economy is hampered by a number of structural issues, particularly for women. According to a 2020 survey by Flourish Ventures, 90% of Indian gig workers experienced income losses due to the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, they made more than Rs. 25,000 per month; by August 2020, they were making less than Rs. 15,000 per month, with more than 33.3% making less than Rs. 150 per day or less. India might lose 135 million jobs as a result of the pandemic, the survey claims. This may drive more full-time workers into the gig economy. These new developments in Indian cities have led to growing ‘informalisation’ in terms of lack of jobs, lack of income security further increase the ‘vulnerability’ weakening the position of labour. A situation of mismatch of skills between informal workers and the availability of jobs in Indian cities is rampant.

Governance Interventions

To aid gig-workers, the government recently passed the “Code on Social Security” 2020 to help gig workers, providing them with advantages like life and disability insurance, accidental injury coverage, health and maternity care, old age protection, and others. In accordance with this code, social security initiatives will be primarily funded by the federal and state governments, with a small contribution from the aggregator (1–2% of yearly revenue). Health coverage worth Rs. 3 to 4 lakh that is extended to families for delivery workers (for 2.3 years as a loyalty benefit) has been put into place as a pilot in New Delhi, Hyderabad, and Ahmedabad. In the meantime, a ‘gig-worker welfare board’ was promised to be established with an allocation of Rs 3,000 crore in the Congress elected programme in the state of Karnataka. A sum of Rs. 4 lakh insurance coverage for gig workers in the state’s budget has been promised. Yet, these welfare measures promised during the elections actually fizzle out after elections. Certainly, at present, there are no reliable governance measures for gig workers.

The Need for Social Inclusion

The gig economy and the formal-informal divide are closely related. These recent changes in Indian cities have contributed to a growing “informalization” in terms of a lack of stable employment and income, as well as an increase in “vulnerability” and economic inequality, which has weakened the position of labour.

The availability of jobs in cities and the skills of informal laborers are consistently out of sync. The political economy trend of unemployment has exacerbated extreme poverty and prevented India’s cities from realizing “demographic dividends,” which are essential for boosting productivity and, in turn, economic growth. While there are numerous opportunities in the gig economy, particularly for city-based migrants looking to make a living and obtain flexibility in their schedules, it is possible that governance policies emphasising social inclusion will be required through improved regulation and state protection.

Dr. K.C.Smitha, is an Assistant Professor, Centre for Political Institutions, Governance and Development (CPIGD), Institute for Social and Economic Change, Bangalore. She is a political scientist, mainly focusing on themes of urban governance, public policy, service delivery, urban poverty, informality, urban political economy and urban political ecology.