The rapid development and severity of the COVID-19 crisis has been a test for governments across the world. As the success or failure of these policies depended on quick and decisive action, the pandemic has also been an occasion to assess the propensity of said governments to enact restrictive policies. In the context of increasing populist and illiberal governments across the world, COVID policies are now at the intersection of protective pandemic policies and restrictive political decisions for populations already sliding down the path of illiberalism. In the context of the recent illiberal wave, the pandemic complicates our understanding of policymaking and pandemic politics, especially in Eastern Europe.

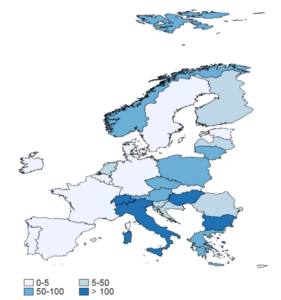

This region encapsulates many of the current world trends as it is located at the intersection of the developed world through its membership in the European Union and the developing world through its difficult transition from Communism to democracy and market economies. Eastern Europe acts as a bellwether for both positive and worrisome trends that could impact other regions. In my work I collected data on populist government duration (in months) and it is clear that Eastern Europe is at the forefront of the populist wave in Europe (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Total duration of populist governments from 1990 to 2018 (in months)

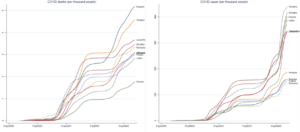

When it comes to the pandemic, this region was once again on the vanguard of global trends. Though Northern Italy experienced the first European outbreak, migrant workers to this country soon began to leave and return to their homes in Eastern Europe. This is how Romania experienced the first official COVID case in Eastern Europe as early as February 26, 2020. According to data from the Johns Hopkins University on cases and deaths, Eastern Europe did experience COVID much sooner than other regions due to its openness to Western Europe (Figure 2). However, when we further examine the data we see that rapid restrictive measures quickly stopped the spread. Figure 2 shows that for most of 2020, Eastern Europe experienced low per capita cases and deaths. At the same time, the fact that the populist illiberal regimes of the Visegrad 4 (Hungary, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia) also experienced the highest per capita deaths compared to other regions seems in line with the reluctance of populists and autocrats everywhere to take COVID seriously, even denouncing it as a “hoax,” while at the same time using this opportunity to further amas executive power under various pandemic pretexts. However, in time the situation changed, with Eastern Europe experiencing higher average COVID deaths per capita than all other regions.

Figure 2: COVID-19 deaths and cases in Eastern European countries per thousand people (January 2020-March 2022)

This situation compelled leaders across Eastern Europe to take action very quickly with some countries adopting measures before experiencing any cases. This was true for Slovakia whose leadership started implementing measures in February with first cases recorded in early March. Many of these countries also instituted states of emergency, school closures and even full-lockdowns early and extensively.

Data from the CoronaNet Research Project records over 100,000 policy entries of governments from 195 countries (Cheng et al. 2020, Kubinec et al. 2021) and as a regional manager for CoronaNet I was in charge of the Western Europe data-collection. Policy types recorded cover actions that regulate personal behavior (wearing masks and social distancing), those regulating institutions (school and business closures), and public awareness measures that seek to educate the public (health monitoring and health resources). The region’s governments display a big variety in policies adopted. While school and business restrictions began immediately (March 2020), masking wasn’t an important policy for Eastern Europe, with the exception of Romania (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Covid Policies in Eastern European countries (Feb 1, 2020-April 29, 2021)

My academic work on this topic explores the role of state capacity in implementing these policies as well as the impact of institutional arrangements on COVID outcomes. However, the impact of populist illiberal policies is still being elucidated. Additionally, as the world starts to focus on pandemic recovery, policies taken during COVID by illiberal leaders could impact the pace of recovery. For example, during the pandemic the right-wing government of the Law and Justice Party in Poland adopted new policies restricting the functioning of the judiciary. A new “Disciplinary Chamber” was created to penalize unruly judges. When the government refused to back down and declared Polish domestic law superior to European law, the country found itself hit with a daily fine of 1 million euro. Although since joining the EU the country has received more than 225 billion USD with an additional 40 billion USD as part of the COVID-19 recovery program, since returning to power in 2015 the Law and Justice Party has maintained an adversarial relationship with the EU which has only exacerbated in recent years.

While the war in Ukraine has taken the spotlight from the pandemic and the democratic backsliding experienced by the region, these issues—though on the backburner—are still progressing on the ground. For example, Viktor Orbán won his fourth consecutive election, continuing a stint in office that started in 2010. The day after his election Orban called the president of Ukraine an “opponent” deciding to focus his first speech of the new government on geopolitical issues rather than the social and economic impact of the pandemic. This is highly problematic as the confluence of populism, policymaking and pandemic politics is likely to impact every day lives of Eastern Europeans for years to come.

Dr. Paula Ganga (Twitter: @PDGanga) completed her PhD at Georgetown University and is currently a postdoctoral fellow at the Harriman Institute at Columbia University. She is working on a book manuscript dealing with the political determinants of switches between privatization and nationalization in Eastern Europe and beyond. Her research focuses on how we view the link between democracy and market capitalism, economic consequences of populism, rising illiberalism in recent political transitions and state capitalism.

Are you currently involved with regional research, policy, and development? The Regional Studies Association is accepting articles for their online blog. For more information, contact the Blog Editor at rsablog@regionalstudies.org.